Margaret Allison

Original owner of Kyoomba Sanatorium

Source: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Source: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Margaret was born on 20 April 1840 at Keir in the County of Dumfriesshire, Scotland. She was the second daughter of John Dunkeld (a farmer) and Anne Newall Brydon.

Margaret’s story begins in 1873 when she immigrated to Australia with a younger brother. They left London aboard the barque ‘Storm King’ on 29 January, arriving at Moreton Bay on 4 May before proceeding to Willson’s Downfall. It was in these parts that Margaret met William Allison (the general store keeper at Sugarloaf Creek) whom she married on 27 January 1874 at the Presbyterian Church in Stanthorpe. For whatever reason, there were no children from this union.

The early years (1874-1890)

Instead, Margaret devoted her intellect, time and energy to supporting and learning from William’s commercial endeavours. Her husband was of an entrepreneurial nature and a successful businessman in the Sugarloaf district. On his untimely death in 1890, Margaret became the owner of several commercial interests, which she expanded with further property acquisitions and investments. In the process, Margaret established herself as a successful business woman and pioneer in the Sugarloaf and Stanthorpe districts.

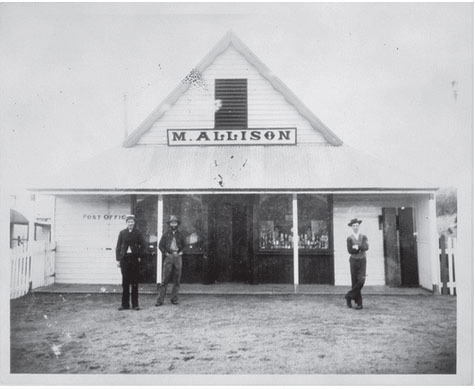

Margaret’s early commercial interests included Allison’s Store, the Sugarloaf Post Office, Allison’s Estate, tin buying, the Sugarloaf Tannery Company, and the Sugarloaf Steam Sawmill. Of these, Allison’s Store was Margaret’s primary source of income and until her death she described herself simply as a ‘storekeeper’. Allison’s Estate merits special mention as this was Margaret’s home and centre of operations for 45 years. In 1881, William selected the homestead under the Crown Lands Alienation Act 1876 (Qld). The 160 acres property (containing a road reservation of 3 acres) was situated about 13 kilometres east of Stanthorpe on the Sugarloaf Road at Sugarloaf. Legally, it was known as Selection/Portion 134 in the Parish of Folkestone.

Allison’s Store, Sugarloaf, post-1890

Source: National Archives of Australia, Barcode 1989336

Allison Homestead

Source: Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 4 March 1904, p. 615

Mining interests (1890-1917)

On her husband’s death, Margaret had inherited several properties throughout south eastern Queensland, including the Allison Estate and Mineral Selection 557 (more commonly known as the ‘Victor Claim’). Mineral Selection 557 (comprising 80 to 100 acres) adjoined the northern boundary of the Allison Estate and was traversed by Sugarloaf Creek.

Both the Allison Estate and Mineral Selection 557 were metalliferous, and Margaret leased the land to miners, buying the tin on royalty for £10 to £16 per tonne. The ore would then be sent to the cleaning mills in Stanthorpe. For many years, Margaret was the largest tin buyer in the Stanthorpe district.

It is not known what motivated Margaret to extend her mining interests. It was likely a combination of factors: a desire to increase her wealth, a rise in the price of tin, the ascension of dredge mining, her ownership of ideally situated freehold land, and encouragement from the assistant government surveyor, Mr. Sydney B. J. Skertchly.

In 1896, Mr. Skertchly visited the Sugarloaf district, lodging with Margaret as he conducted a geological survey for the Queensland Department of Mines. During his visit, a small lode of silver and gold was found on Block 406. Block 406 was on the eastern boundaries of the Allison Estate and Mineral Selection 557, and was acquired by Margaret in 1895. After publication of Mr. Skertchley’s report, Margaret decided to invest in alluvial tin dredge mining. In 1900, she engaged shipwrights to build her two dredges, and by the end of 1904, Margaret’s dredging operations were known as one of the largest and richest in the Sugarloaf district.

In 1906, Margaret capitalised on this reputation by leasing the right to mine her creeks and alluvial flats to a Melbourne syndicate. On expiration of that contract, she again leased the mining rights, this time to a London syndicate. In 1911, Margaret resumed her own dredge mining operations. With capital to invest, she purchased two barge dredges. The first was a Thompsons hydraulic sluicing plant, which was in operation for only a few months when an unknown person attempted to destroy it by placing gunpowder or dynamite in the boiler’s fire box. The second barge dredge was manufactured by the Phoenix Foundry at Ballarat, Victoria. It was ‘easily the largest on the field and practically new’ when it came into operation in 1914.

The two barge dredges worked various locations at Sugarloaf Creek, including the junction at Browne’s Gully. Although Margaret’s property was considered capable of supporting two more dredges, she only acquired one more, which was placed at her property at Kyoomba.

Commercial real property interests (1900-1919)

Margaret steadily built her reputation, wealth and standing. In addition to business and mining, Margaret also developed several interests in commercial real property. She was particularly concerned with the town of Stanthorpe and in supporting the advancement of women. It is unfortunate that Margaret has not been remembered for these contributions. However, at the turn of the 21st century, Margaret’s influence was everywhere. Margaret’s first venture into commercial real property was the construction of new premises for the Royal Bank of Queensland, Stanthorpe Branch (1901).

Royal Bank of Queensland, Stanthorpe Branch, 1904

Source: Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, Stanthorpe Show, 4 March 1904, p. 615

Shortly thereafter, Margaret commenced a new project, purchasing 12 Maryland Street for the construction of a row of five shops and three offices (the Allison Building, 1904).

In 1928, a fire broke out in one of the shops. The alarm was immediately raised and a volunteer bucket brigade was quickly organised. However, the fire had taken hold and there was no hope of saving the Allison Building. Within six months, Margaret’s nephew, John Gordon had arranged for the construction of a new building. The two-storey brick building with five ships was said to be an ‘architectural feature…with an impressive and attractive front elevation and [internally] possessing details of the most modern character’ (Cairnsmoor Building, 1928).

Margaret also owned the premises at 27 Maryland Street which was leased to the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney. In 1914, a ferocious fire destroyed this property together with several other buildings. The following day only brick chimneys were left standing amid the smouldering ruins.

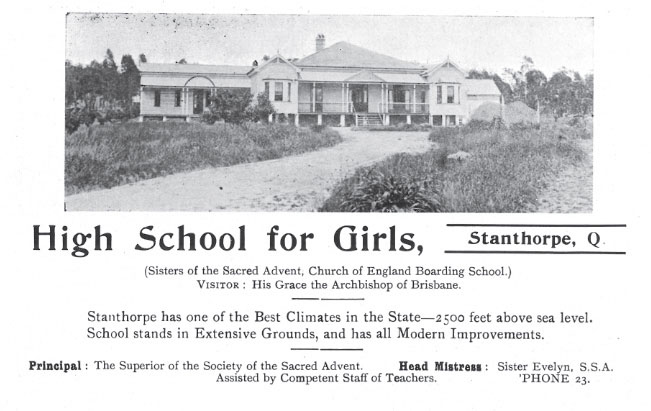

Margaret did not rebuild at 27 Maryland Street, retaining it as an empty allotment until it was eventually sold to the Commonwealth Bank of Australia in 1934. Following completion of the Allison Building, Margaret was approached by a Miss Violet Gibbins to construct a ladies’ boarding school at Stanthorpe. Margaret agreed and purchased 200 acres of land that had previously been part of the Hon. Mr. Justin F.G. Foxton and Mrs.

Emily M. Foxton’s ‘Sentimental Rocks’ property. Within six months, the school which was named Cambridge Ladies’ College had been constructed and was accepting students. At the outset, there were high expectations for the success of Cambridge Ladies’ College. However, in mid 1907, Miss. Gibbons’ successor, a Mr. George F. Elkington, claimed that the number of students and income of the college were low. He alleged that Margaret had misrepresented the situation to induce him to purchase the business and goodwill from Miss. Gibbons.

Over several days, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Queensland, Sir Pope Cooper, and a four-man jury heard the case of Elkington v Allison. Although all but one witness spoke highly of Margaret (describing her as ‘thoroughly honest and straightforward’), the jury quickly decided the case in Mr. Elkington’s favour. Margaret promptly sold or released the real property to a Miss. Hannah England, who operated the school for less than two years, before it was acquired by the Sisters of the Sacred Advent, St. Catharine in 1909. Margaret continued to support the school by attending regular functions and on her death, bequeathed £100 to the principal to purchase prizes for meritorious students.

Cambridge Ladies’ College (later renamed the High School for Girls, then St. Catharine’s School, Stanthorpe), c. 1910

Source: L.T. Jobson, Souvenir of the town of Stanthorpe: with its mountain beauty spots, orchards, mining country, including precipices streams and waterfalls, Brisbane, 1910.

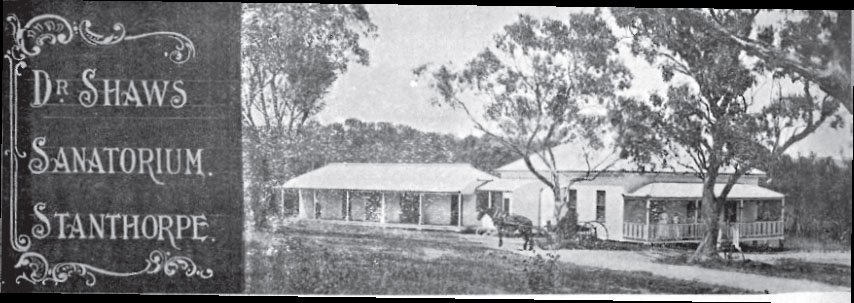

Recently, there has been great interest in another of Margaret’s projects, the Kyoomba Sanatorium. It is not clear how Margaret came to build the Sanatorium. However, she was likely approached by a young lady doctor who had recently commenced practice in Stanthorpe, Dr. Helen Shaw. In 1906, Stanthorpe was widely considered the ‘sanatorium of Queensland’, and its high elevation and generally dry climate were ideal conditions for the treatment of tuberculosis.

Margaret agreed to build a sanatorium on her Kyoomba property for Dr. Shaw to privately treat tuberculosis patients. In 1907, the architect, Mr. Hugh K. Campbell, called for tenders for ‘building and erecting a sanatorium, near Stanthorpe, for Mrs. M. Allison’. Interested builders were invited to view the plans and specifications, and by year’s end, the Kyoomba Sanatorium was open for business.

Kyoomba Sanatorium, c. 1910

Source: L.T. Jobson, Souvenir of the town of Stanthorpe: with its mountain beauty spots, orchards, mining country, including precipices streams and waterfalls, Brisbane, 1910

The Kyoomba Sanatorium was privately operated for several years. However, when Australian servicemen began returning from the Front during the Great War, Margaret made the Sanatorium available to the Red Cross Society for repatriation purposes. It then functioned as a tuberculosis hospital.

Although this arrangement was intended to last for the duration of the war, the Red Cross Society found the hospital too great a responsibility and asked the Commonwealth of Australia to assume control, subject to Margaret’s approval. That approval was given in March 1917 and the Kyoomba Sanatorium acquired a new name–the ‘Stanthorpe Military Sanatorium’. In mid-1918, Margaret sold the Stanthorpe Military Sanatorium to the Commonwealth Department of Defence. The terms were described as ‘very liberal’ and in 1921 Margaret was paid £2995 for her interest in the property.

Although an astute businesswoman, Margaret was also concerned with the provision of care for sick and vulnerable people. In addition to the Sanatorium, she supported the local hospital and on her death gifted £100 each to the Lady Lamington Hospital for Women, and the Blind Deaf and Dumb Institution, both at Brisbane. Demonstrating an awareness of, or affection for, the country of her birth, Margaret also gifted £50 to the Parish Church in Dalry, Dumfriesshire for the purchase of coal for the poor.

Later life

Margaret was well aware of her own mortality. From 1918 she began to put her affairs in order through the creation and endowment of a corporate entity—Allison Company Limited—and by executing her last will and testament.

Margaret died on 24 January 1926 after being in poor health for some years. The Supreme Court of Queensland granted probate in her Estate in 1927, and over the next few years, Margaret’s executors realised her assets. The magnificent Allison Estate (by then known as the Sugarloaf Estate) was sold to a Mr. Michael Dillon for £4769 9s in November 1929. John Gordon was Margaret’s sole heir.

In accordance with her wishes, Margaret was buried at Stanthorpe Cemetery with her husband, five siblings and another nephew, James William Henry Gordon (younger brother of John), all of whom predeceased her by many years. Their graves are marked by a single granite headstone imported from Scotland and bordered by an ornate metallic fence depicting Scottish thistles. John Gordon is buried close by with his wife, Mary Avery ‘Doll’ Passmore, and her family.

Read about Kyoomba here.